“Tango Argentino” — The Show That Brought Tango Back to Glory

Tango history often hails the 1930s to the mid-1950s as the “Golden Age” of Argentine tango.

Some would even say that these golden years began earlier, with celebrities such as Rudolph Valentino popularizing tango on the big screen with the 1921 blockbuster, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

Similarly, Ovidio José Benito Bianquet, more popularly known as “El Cachafaz”, was cemented into tango history through the 1933 film Tango. Along with his dance partner, Carmencita Calderon, El Cachafaz graced the big screen with his performance, which was often remembered for its display of intricate footwork.

As these movies and many others reached wide audiences in the Western world, the interest in tango grew by leaps and bounds. Argentine tango was no longer confined to social dance halls.

Even though its initial reception among the conservatives in Europe and North America sparked a measure of social outrage due to its supposed scandalous nature, the Argentine tango soon became a phenomenon that transcended even social classes.

Of course, the fact that the Roaring Twenties was a time of prosperity for America gave way to tango’s ever-increasing popularity. Even after the Great Depression and the Second World War, tango continued to capture the interest of audiences and aspiring dancers. Due to its origins in the brothels of Buenos Aires,

it was not hard to imagine that tango continued to thrive despite the dire social conditions that came before and after the war.

In fact, it may have been its humble origins that allowed it to flourish amidst societies that needed recreation as a way of coping with the war’s aftermath.

Like any concept that has reached its peak, however, Argentine tango was not immune to the plateau regarding its popularity. By the mid-1950s, other activities and forms of music were beginning to gain ground among audiences, which the media began to focus on. Thus, Argentine tango was relegated to the backseat — at least until its revival in the mid-1980s.

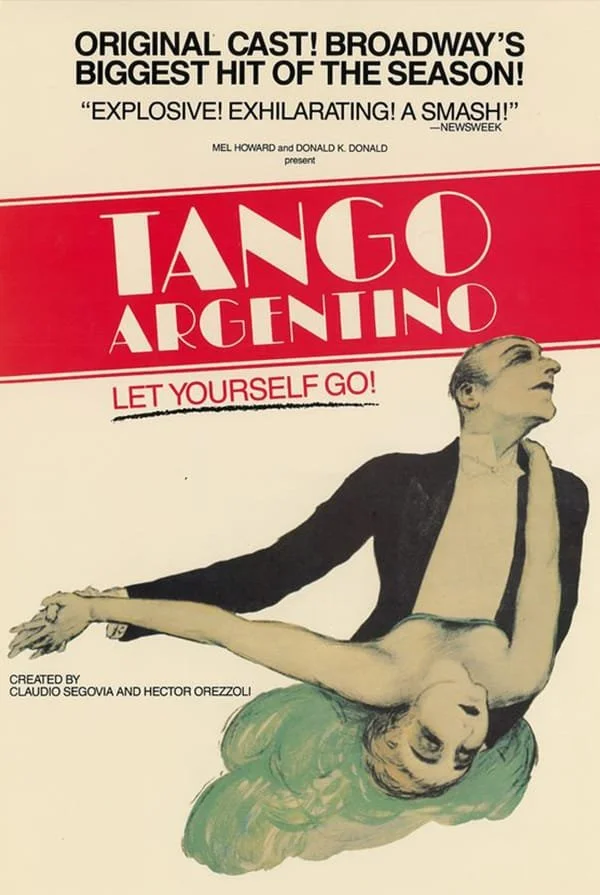

At that time, one tango show would put tango back on the map: Tango Argentino.

The Unlikely Hit

Marissa E. Guillén’s The Performance of Tango: Gender, Power and Role Playing provides a summary of how Tango Argentino made this possible:

“Although tango fell out of vogue for a few years, it reemerged as a cultural phenomenon with the production of Tango Argentino.

Juan Carlos Copes and his partner Maria Nieves assembled some of their fellow tangueros in a musical revue of tango in 1983, which developed into the Broadway hit Tango Argentino. Originally produced in Paris, before arriving in New York,

Tango Argentino awoke the excitement of people who saw it. The revue featured some of the most prominent tango artists, including musicians, singers, and dancers, displaying their talents and the variety within tango.

“Tango became less prominent in the media, appearing only anecdotally in the years prior,

but after the arrival of Tango Argentino, the word tango dotted The New York Times. The show stirred much public interest and puff pieces. People wanted to know more about the history, use of tango, as well as how to achieve the look.

In this way, Tango Argentino spawned a cultural industry of tourism, lessons, and fashion similar to the tango craze of 1914. [Robert Farris] Thompson observed,

‘The reasons for its success were clear: people savored the mixture of music and text, singing and dance, in what was self-evidently one of the richest offerings of national talent on the planet.’

Simple staging and monochromatic costuming focused the spectacle on the tango itself. Because it was so different, Tango Argentino energized the 1985-86 Broadway season.”

Tango Argentino’s success was actually quite unprecedented.

It struggled to acquire sponsors and investors as tango had gone from being a phenomenon to being viewed as something tacky within the shifting social landscape. The production also did not have the budget of typical Broadway shows, which meant that costumes and other production paraphernalia were quite limited.

However, despite this and other obstacles, Tango Argentino’s success was not at all surprising to the media.

It was no secret that Broadway often produced unlikely hits. A New York Times article by Samuel G. Freedman, specifically referenced in Guillén’s thesis, had this to say about the Broadway production of Tango Argentino when it dazzled audiences in October 1985:

“Even on Broadway, where musicals about felines and female impersonators can become hits,

Tango Argentino arrived in October as the longest of shots. Here was a show, after all, that violated the Broadway dictum that musicals be elaborate, expensive, and stocked with supple young bodies. Tango Argentino wasn't even in English.

“Ten weeks later, this evening of tango song and dance has not only become the unlikeliest hit of the season but has also inspired a popular culture craze unmatched by any Broadway show since The Boy Friend. What the 1954 musical comedy did for the Charleston and the flapper's chemise, Tango Argentino has done for slit skirts, silk scarves and male dominance, at least on the dance floor.”

What was perhaps the most charming aspect of Tango Argentino was that, like the dance itself, it defied what were norms at the time, particularly in stage productions.

Many of the tango couples featured in Tango Argentino were middle-aged, though this only served to intensify the groundedness and emotionality that marked the musicality and themes surrounding Argentine tango.

These themes often consisted of heartbreak, social conundrums, and even death. Juan Carlos Copes, who put the show together alongside directors Claudio Segovia and Hector Orezzoli, was one of the dancers hailed for embodying the elegance and artistry needed to portray these themes.

According to a post from Dance International:

“Copes was 52 in 1983, and his equally celebrated partner, Maria Nieves, was not much younger. They had been dancing together for more than 30 years, a married couple for nine of them. Neither had formal training — tango in their day was learned in dance halls — yet both were highly conscious of how to present their body lines.

Supremely elegant, Copes had a distinctive soft step and economy of movement that never betrayed effort. Despite considerable marital woes, Copes and Nieves on stage displayed remarkable respect for each other, which translated visually into choreography of great dignity. Dignity defined not only their serious numbers but their humorous ones, as well.

Tango Argentino audiences discovered that along with battle-of-the-sexes passion, tango had a comic side and could accommodate different moods and situations.”

Since the production was also on a budget due to its difficulty finding sponsors and investors,

Tango Argentino did not display the usual bombastic spectacle expected of typical Broadway shows. In fact, the costumes of the tango dancers remained monochromatic — a combination of white, black, and silver.

While some may deem this disadvantageous at the onset, it was precisely because of this lack of gimmickry that audiences were able to truly focus on the unscripted narrative and appreciate the energy and passion of the improvised choreography.

In the same article from The New York Times, Orezzoli himself was astonished at the reception the show obtained from audiences:

"'We couldn't imagine it would find such a large audience who would react in such an emotional way,' Mr. Orezzoli said. 'I have people come up to me and say, "I have dreamed all my life of the tango." It is like they have seen God.'"

For Show or For Real?

However, as with many concepts that have been popularized in the West, Tango Argentino was not entirely welcome in tango’s very own home country, Argentina. In fact,

the performances from Tango Argentino were considered by those in Buenos Aires as "stage tango" or "show tango," which is often understood in a derogatory way among older milongueros.

To them, show tango or "tango for export" is seen as diminishing the true essence of tango. So-called real tango is not meant to please audiences but done for the personal pleasure of the dancers themselves. Flashy moves that occupied a lot of floor space were viewed with derision as this did not exactly portray the kind of tango being danced in milongas, which usually had limited space. Thus, many milongueros felt that tango for export was doing "real" Argentine tango a disservice.

Further explaining the concept of tango for export is this post from Tango Voice:

“‘Tango for export’ is a synonym for stage tango. It is the tango stage shows of the 1980s and 1990s, such as Tango Argentino, Tango x 2, and Forever Tango traveling around the world that were the primary vehicles for transmission of an aspect of Argentine tango culture to the rest of the world.

The terminology ‘tango for export’ is often used in a derogatory manner by social tango dancers in Buenos Aires to designate it as not representing the way Argentines dance tango socially, in contrast to the way social tango in other countries borrows heavily from exported stage tango.”

Forever Tango - A Evaristo Carriego - Carlos Gavito & Marcela Duran

While tango for export was viewed unfavorably among those who considered themselves authentic tango dancers, there’s no denying that the same show tango they seemed to reproach paved the way for Buenos Aires to capitalize on tango as a tourist commodity.

It was also timely that the dictatorship in Argentina was no longer in power during the mid-1980s, allowing tango to once more flourish in an environment that let everyone participate.

Entangled Tangos: Passionate Displays, Intimate Dialogues by Ana C. Cara explains the prevalent sentiment the Argentines in Buenos Aires had about Tango Argentino:

“The international success of the spectacle... rekindled among Argentines the power of tango as dance. It fueled, on the one hand, the ambition of impresarios who began crafting tango shows for export and tourism. And it stimulated, on the other, tango dancing among ordinary folks at home, after a period of abstinence during the Argentine Dirty War (1976–83).

Unlike international audiences, however, Argentine dancers responded not to the formulations of an exotically marked passionate tango but to the recollection of traditional notions of tanguedad (tango ethos), practiced on local dance floors rather than on stage.”

As such, even with its international success, Tango Argentino would not debut in Buenos Aires until 1992. According to a report from the Los Angeles Times:

“Though Tango Argentino summarizes the development of one aspect of Argentine popular culture and has inspired worldwide interest in both tango dancing and the performers who still maintain the authentic tango traditions, the show has never been seen in its country of origin. No sponsor was interested.”

The same report revealed that Orezzoli, one of the directors, was invited to bring Tango Argentino to the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires but he had not accepted it at the time. Quoting Orezzoli, the article states:

“‘Their values really haven’t changed toward the tango or anything that is authentic or identifies us,' he declares. 'We would like to do it (in Buenos Aires) but not in an official theater for an elite that doesn’t understand and has never been interested in this kind of artist.’”

No Guts, No Glory

In many ways, the odds were against Tango Argentino being an international success. After all, the 1980s saw the emergence of new wave and electronic dance music, which seemed worlds apart from the traditional and exotic sounds of the bandoneon.

Considering the logistical and financial challenges it faced, one can perhaps say that Tango Argentino was more of a passion project than anything else.

Those who worked on the production did not seem to be concerned with the returns; rather, they simply wanted to showcase Argentine tango to a bigger audience.

Regardless of one’s opinions about its authenticity, one thing is for sure about Tango Argentino: If not for its guts, tango would not have reclaimed its glory.